27.07.21

27.07.21

Commissioned by the IAF, the review of Noreile Breen’s installation was written by Colm Ó Murchú who took part in our inaugural Emerging Architecture Writers (EAW) programme, run alongside Momentum.

by Colm Ó Murchú

It is a typical Dublin summer day; the rain is falling in abrupt bursts and it is uncomfortably muggy. A curious tripod-mounted reflective funnel is confined to the small reception area of the Irish Architecture Foundation’s Bachelor’s Walk premises, its ‘head’ swivelled towards the window as if in anthropomorphic dismay that rain has stopped play. This strange device, when weather allows, sits on the steps of no.15, arcing incrementally with the path of the sun above to keep its funnel in constant illumination, capturing the curiosity of passers-by. The apparatus is from the mind, via the workbench, of architect and maker Noreile Breen.

Its placement out on the street is in contrast with the other exhibits, rooted in their respective rooms. They are inherently static contemplations, whereas with Breen’s piece, you are imagining where it might go. I resist the urge to collapse the legs, throw it over my shoulder, and march on to the quays. Breen’s submission is set apart by its dynamic nature; it invites you to manipulate it by presenting the irresistible allure of a handle or a lever (I was earlier admonished for touching plattenbaustudio’s perfect paper installation). It is simultaneously tactile and fragile, bearing the hallmarks of a working prototype, an improvised device with just enough precision to test a concept.

Breen is known for her work in the study of light and colour. Her contributions to the Venice Biennale in 2018 drew much comment, her study model of Luis Barragán’s Casa Ortega a self-described ‘instrument for looking, training the eye to see’.

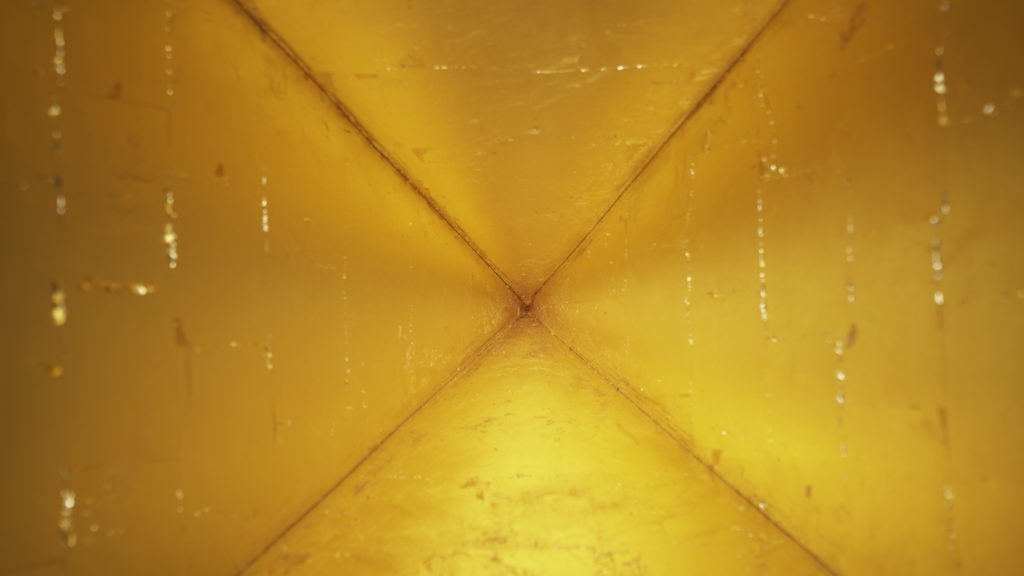

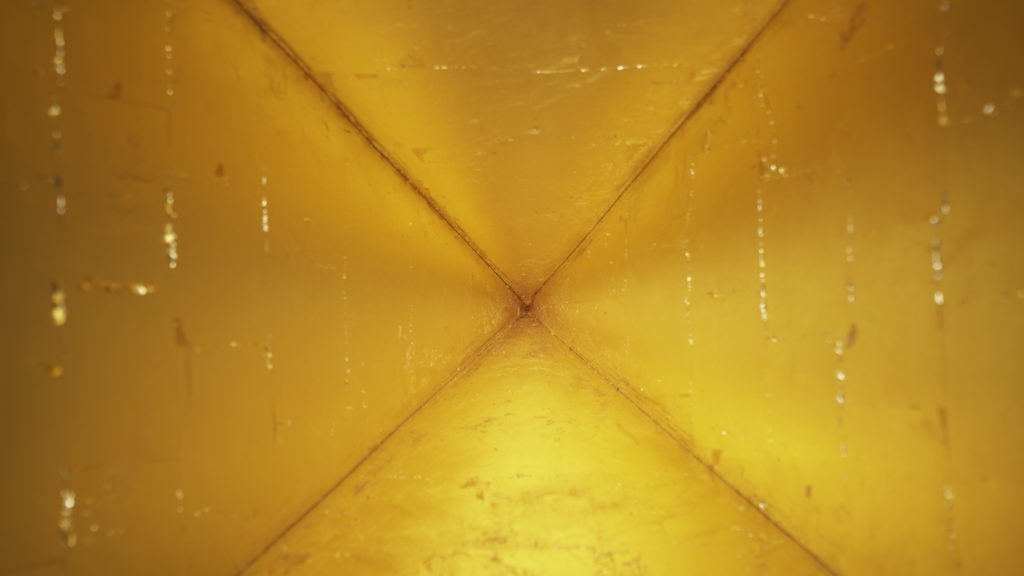

Contemplating her latest instrument, the striking gold leaf is reminiscent of the foil-like heat shields of spacecraft, its tripod particularly like the appendages of the Voyager probes sent by NASA into deep space in the 1970s to collect data on our solar system and beyond. Perhaps we could send it out into the city, in search of life, to make contact. Maybe we could keep vigil, sat atop the building, and wait to see what it might reflect back to us.

Voyager 1 and 2 contained etchings and recordings that, if discovered by another intelligence, might give them some clues about our world. What would another life form discern from Breen’s piece? The materials would indicate the composition of our Earth and its environment. The proportions of the apparatus, the handle and grips, would give vital clues as to our bio-mechanics.

But what could this artefact tell others about our aspirations? They might divine from its reflective nature that we orbit a light-emitting source, crucial to our survival. The rotating head might suggest that we go to great lengths to turn our faces towards it. From the wafer-thin leafs of gold, others would understand what we commodify, what is precious and used sparingly. The funnel would indicate that we are constantly trying to harness some force, concentrate it, absorb it. They might infer that our existence is fragile, that we live in delicate circumstances, constantly adapting, looking for new resources, craning our necks to soak up a little more of something.

Speaking on the podcast What Do Buildings Do All Day?, Breen tackled the description of her and fellow panelists as ‘emerging’ architects. Breen expresses her wish to stay in a perpetual state of ‘emergence’, constantly transitioning or travelling to somewhere. She describes her approach to practice as akin to burrowing through a peat bog.

She has surfaced here, briefly, granting me an audience via Zoom. Breen is keen to stress from the outset that the apparatus is ‘nothing more than a dumb object’ built with just enough care to allow her to get closer to reality. She notes a recurring pattern in her work: experimentation, improvisation only to the point of proof of concept. Rarely finished, these ‘instruments for understanding’ as she describes them, are quickly set aside once all has been gleaned from them.

Our conversation is one of joyous digressions. Breen shares one anecdote in particular that resonates, about a neighbour of hers in rural Kerry, a farmer who has built his own weather station. This autodidact meteorologist is now a more trusted source for weather forecasting in his locality than the national broadcaster. Weather forecasting is not his product, but it has become integral to his work, to the point where he has become an accidental expert, like a really engaging sub-plot in a wider, duller story. Abruptly, she begins rummaging somewhere off-screen, reappearing with a black box, which she deftly dismantles and holds up to the screen, showing me its rudimentary inner workings. It’s a box camera, she explains, a Kodak design from the early 1900s. The camera, of course, is not the work. The photograph is the work, the camera is simply the tool, but for Breen, the delight and wonder is in the tool. It is a simple, revelatory moment between us. Breen’s submission is not the work, it is the tool, one she has set down for just a moment, allowing us to examine it. The work, if you’re patient, you will see emerge in Breen’s schemes to follow.

Afterword

On the hottest day of summer so far, Breen and I play a cat-and-mouse game of missed texts and shifting rendez-vous across the city. When we finally meet, she is standing on a quiet street corner in Drumcondra. The head of the apparatus is lying on the footpath at the end of a typical Dublin terrace, golden and proud against the dulled and patchy red brick of the gable and the weeds growing through cracks in the pavement. The setting sun has aligned with the street, funnelled between the houses, filling the awaiting golden receiver. It begins to alter the depth-perception of the viewer, moving from a uniform square of light to a visual anomaly, a portal without position, eschewing the X, Y, and Z planes of our world. We stand and wait to see what might emerge.

Colm Ó Murchú is a graduate architect working in Waterford and living in his native Carlow. Colm received a B.Arch from Waterford Institute of Technology in 2019 and is currently working towards his Prof. Dip. in Architecture at UCD.

For more information on our Emerging Architecture Writers Programme click HERE

27.07.21

27.07.21